It’s 2010, and Laura Ricketts is at a knitting conference at Seattle’s Nordic Heritage Museum. She’s looking at a display of national costumes, absorbed by the “beautiful, clear blues” of the Sámi pieces, when a question pops into her head: “Where is their knitting?” Why hasn’t she heard of it or seen it, like Swedish twined knitting or Norway’s Setesdal sweaters?

It’s 2010, and Laura Ricketts is at a knitting conference at Seattle’s Nordic Heritage Museum. She’s looking at a display of national costumes, absorbed by the “beautiful, clear blues” of the Sámi pieces, when a question pops into her head: “Where is their knitting?” Why hasn’t she heard of it or seen it, like Swedish twined knitting or Norway’s Setesdal sweaters?

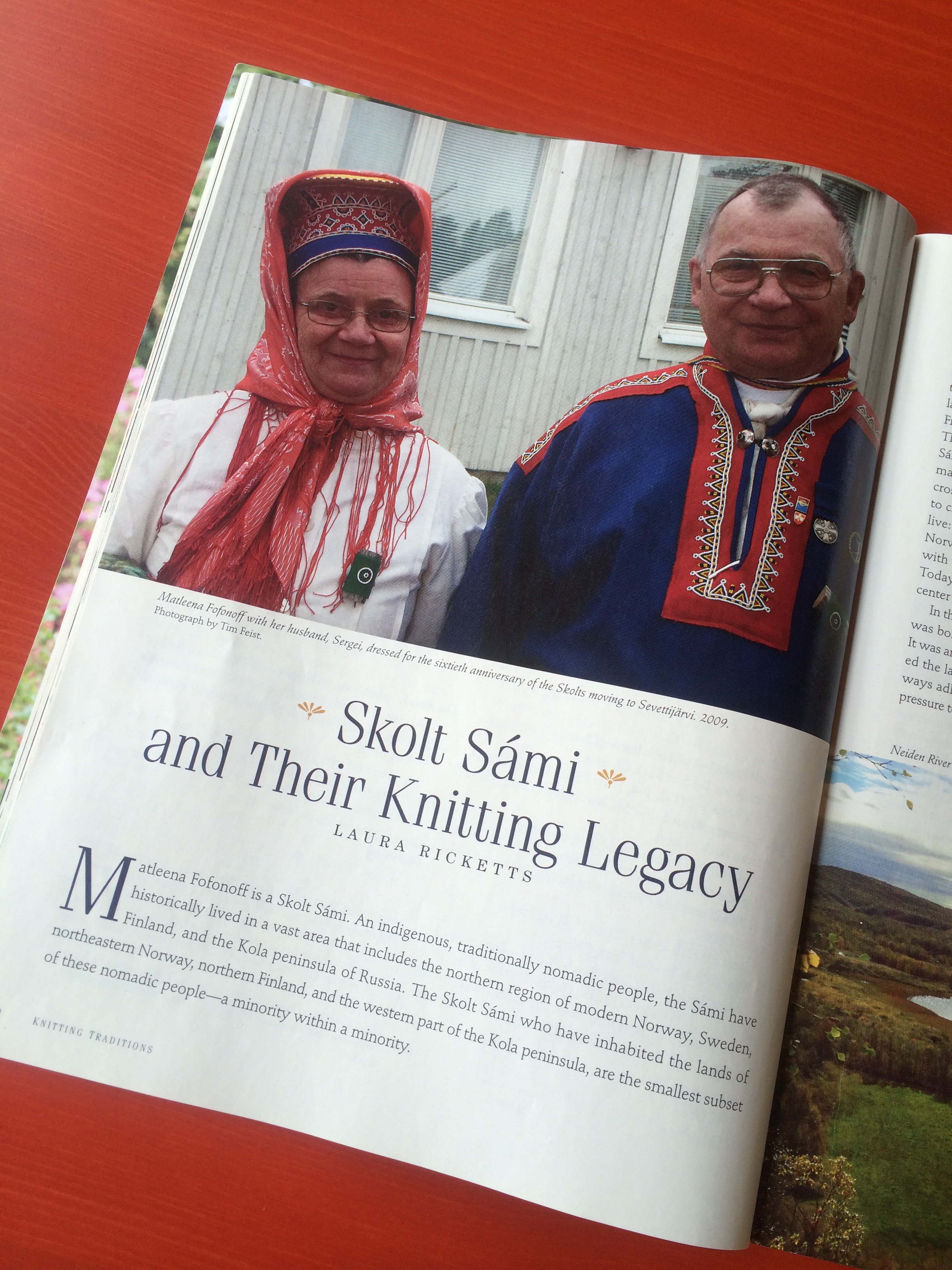

Four years later, Ricketts knows at least some of the answers to her own question, and she’s sharing them in her article “Skolt Sámi and Their Knitting Legacy” in the fall issue of Knitting Traditions, and in more teaching engagements this fall at the Vesterheim Norwegian American Museum in Decorah, Iowa, and back at the Nordic Heritage Museum where her journey began.

Four years later, Ricketts knows at least some of the answers to her own question, and she’s sharing them in her article “Skolt Sámi and Their Knitting Legacy” in the fall issue of Knitting Traditions, and in more teaching engagements this fall at the Vesterheim Norwegian American Museum in Decorah, Iowa, and back at the Nordic Heritage Museum where her journey began.

But the story of Sámi knitting wasn’t easy to tease out from the misperceptions about it, or from the Sámis’ history as a fragmented and suppressed minority culture.

But the story of Sámi knitting wasn’t easy to tease out from the misperceptions about it, or from the Sámis’ history as a fragmented and suppressed minority culture.

“Universally,” when Ricketts started to research and ask her questions out loud, “everybody answered me and said, ‘[The Sámi] don’t knit. They herd reindeer. They wear reindeer skins. You can’t spin reindeer fiber, blah, blah, blah.’ And I just thought, ‘Hmmm, it doesn’t completely make sense that these people living in the far north and living next to the Norwegians and the Finns and the Swedes wouldn’t have any knitting at all.’”

Who are the Sámi?

They’re the indigenous people whose homeland, Sápmi, stretches across northern Norway, Sweden, Finland, and into Russia. They speak a language that’s related to Finnish. To knit is gođđit. Handcraft is duodji. There are 10 dialects, though several are extinct or nearly so, with just a few hundred speakers. Like other native people around the world, the Sámi have experienced discrimination and the majority Nordic cultures of recent centuries have used legal and economic pressure to force Sámi people to abandon their culture, give up their land, and assimilate. That tide began to turn in the 1970s.

It’s true that many Sámi have been reindeer herders and used hides to dress warmly. In Norway, where the highest number of Sámi are found, almost 3,000 people still herd reindeer for a living. About 40 percent of Norway’s land is in use as reindeer pasture. But there have always been Sámi who depended more on fishing, hunting, trapping, and farming over time, and now the majority live in cities, doing the same kinds of work as everyone else.

It’s true that many Sámi have been reindeer herders and used hides to dress warmly. In Norway, where the highest number of Sámi are found, almost 3,000 people still herd reindeer for a living. About 40 percent of Norway’s land is in use as reindeer pasture. But there have always been Sámi who depended more on fishing, hunting, trapping, and farming over time, and now the majority live in cities, doing the same kinds of work as everyone else.

Hiding underneath that perception that the Sámi have relied solely on their reindeer is where Ricketts found a knitting tradition.

“People would wear reindeer mittens, but it’s a little bit uncomfortable to just wear a reindeer mitten and have the seams on the inside. So historically, before there was knitting, they would use a sedge grass that they had softened” as a lining, she says. Knitted mittens eventually served the same purpose.

“Sámi knitting has basically been just mittens,” Ricketts says, though the Skolt Sámi, concentrated mostly in Finland, have also had knitted stockings. The work is similar to other Nordic knitting in that it’s stranded—especially dress mittens and especially around the cuff. The colorwork is usually done against a ground of natural white and some common Nordic motifs appear, such as the eight-petaled rose or star. Work mittens are typically plain and made in natural grays, browns, and blacks.

“The majority of the Sámi mittens have an open cuff, they don’t have a ribbed cuff,” Ricketts explains. That was so a herder could shake a mitten off quickly to get better use of his hands. “The exception is that people who worked in fishing areas would have a ribbed cuff.” Even when their mittens got wet, they wanted that insulation on their hands.

A second difference from other Nordic traditions “is that almost universally, all of the thumbs are ‘peasant thumbs,’” Ricketts says. That’s a thumb worked without any shaping on the hand to accommodate it, also called an “afterthought thumb.” There are no stitch increases to form a gusset below the thumb, so the pattern motif on the palm is never disrupted. “You can follow it uninterrupted and finish your mitten, then come back and do your thumb and make your thumb match the palm exactly. So that when your mitten lies flat, sometimes you can’t even see where the thumb is because it blends into the fabric.”

A second difference from other Nordic traditions “is that almost universally, all of the thumbs are ‘peasant thumbs,’” Ricketts says. That’s a thumb worked without any shaping on the hand to accommodate it, also called an “afterthought thumb.” There are no stitch increases to form a gusset below the thumb, so the pattern motif on the palm is never disrupted. “You can follow it uninterrupted and finish your mitten, then come back and do your thumb and make your thumb match the palm exactly. So that when your mitten lies flat, sometimes you can’t even see where the thumb is because it blends into the fabric.”

That gives Sámi and Latvian mittens something in common. Also like Latvian mittens, Sámi mittens have braidwork around the cuffs.

That gives Sámi and Latvian mittens something in common. Also like Latvian mittens, Sámi mittens have braidwork around the cuffs.

“There’s almost always a four-strand braid hanging off the cuff, and a tassel at the end,” Ricketts says. The extra length of braid is for hanging the mittens to dry near the fire, “or tie them together and hang them from the harness of a reindeer. It helped keep them together.”

After lots of research at a distance, last fall Ricketts got to travel across Sápmi to view museum collections and meet with Sámi knitters. She took 3,000 pictures of all the mittens she saw “and I’m writing up patterns.”

The knitting of the Skolt Sámi gained her special affection because “they are the only Sámi knitting that retains some of the names to their patterns. The pattern names are tied to a lot of the things they experience in everyday life”—“Stone in the Pond” and “Ptarmigan’s Foot.” In a bit of utilitarian grace, Skolt mittens have extra stitch decreases at the inside tip of the hand and thumb to make them cup inward, mimicking the natural curve of the wearer’s hand.

The knitting of the Skolt Sámi gained her special affection because “they are the only Sámi knitting that retains some of the names to their patterns. The pattern names are tied to a lot of the things they experience in everyday life”—“Stone in the Pond” and “Ptarmigan’s Foot.” In a bit of utilitarian grace, Skolt mittens have extra stitch decreases at the inside tip of the hand and thumb to make them cup inward, mimicking the natural curve of the wearer’s hand.

Skolt Sámi motifs are what Ricketts will teach in her August 9 class, using Rauma Vamsegarn, a worsted weight similar to the yarns spun and used by Sámi knitters—at least what they used historically.

A former high school history teacher who lives in Indiana, Ricketts knows that what she’s found is a Sámi knitting tradition in its historical form. Just as with their homes, work, and clothing, what present-day Sámi knit might be indistinguishable from what anyone else likes to knit.

A former high school history teacher who lives in Indiana, Ricketts knows that what she’s found is a Sámi knitting tradition in its historical form. Just as with their homes, work, and clothing, what present-day Sámi knit might be indistinguishable from what anyone else likes to knit.

“I’m also very careful in what I say, because I’m not Sámi and I’m speaking about the culture as an outsider,” she says.

She wants to keep piecing together a picture of Sámi knitting before the bits of tradition that remain disappear. “I’m hoping just to make a note of the history and allow the information not to die out,” Ricketts says. “If anyone reads this or hears about it and knows stuff, please contact me because I’d love to chat.”

She wants to keep piecing together a picture of Sámi knitting before the bits of tradition that remain disappear. “I’m hoping just to make a note of the history and allow the information not to die out,” Ricketts says. “If anyone reads this or hears about it and knows stuff, please contact me because I’d love to chat.”

Think of it this way: Laura Ricketts went to Sápmi to learn a dialect of knitting. With her teaching and her writing, she’s adding her voice to those of Sámi knitters to keep this language from going extinct.

—Denise Logeland

Denise, Thank you for your very interesting blog…keep those articles coming.

Thank you, JoAnn! I’m fascinated by what Laura is doing and hope others will be, too.

Denise

Great article Denise, I am looking forward to the class on Saturday!

So glad you can come, Evonne! I hope to sit in, too. Isn’t Laura’s work interesting? Thank you for the kind words.

Denise

I sadly cannot come to the class, but your post of it certainly is inviting and informational. I have thoroughly enjoyed your blog posts and look forward to them.

That’s a day-brightener, Joyce. Thank you for the encouragement. I have a lot of fun working on these posts, and it’s so nice to know that others have fun with them, too. And aren’t we lucky to have people like Laura around, giving us a window into things we all like to read about?

Very interesting, as I wanted to make a sweater using some Sami patterns.

Hello, I’m very interested in learning how to knit traditional Scandinavian, most especially Finnish crafts. My dear Father was Finnish/born in Canada, I guess that makes me 1/4 Finn? The beautiful Scandinavian culture has interested me since I was very young. One day I hope to knit a pair of traditional Finnish mittens.

I’ve been admiring your blog, keep up the great work!

Thanks so much for your kind comments.

I am Saami woman and I do not appreciate those that go to our museums and into family homes and take pics of our handicraft and later sell the patterns (which they do not own the rights to) on the Internet. By doing so she actually contributes to the massive reproduction of false Saami handicraft which undermines the income of those Saami that has handicraft as a income source for their livelyhood. In addition she uses family patterns which have taken generations to develop and though it might seem like similar mittens for her they actually give information about which area, which gender and family the knitter comes from. In addtition she is a self proclaimed expert and teacher in an area she does not have any knowledge in depth of. It is nothing less than abusive. I would like to remind her that The UN Declartion of Indigenous Peoples rights article 31 which states that it is the indigenous people (in this case the Saami People) that own the right to the patterns not this American woman. She could focus on all other patterns there are in the world and not on our traditional Saami patterns.

Do you sell photo prints of your work to be framed, I love the one where your mittens are like a wreath. Thanks, Chris Cloutier