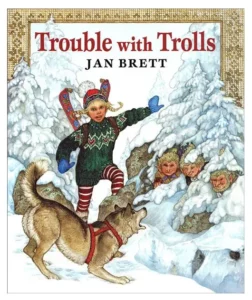

The original tales of Norwegian trolls are stories of giant beings that roam the mountains and forests and spend their days hiding from the sunlight. What happens when the sunlight hits them? They turn to stone! Maybe that’s why they are often connected with the cold winter months and the holiday season, so they can roam freely in the dark cloudy weather. One of my first introductions to trolls was Jan Brett’s book, The Trouble with Trolls. While at her winter cabin, Treva and her dog Tuffi have to navigate these pesky mountain dwellers.

I thought this would be the perfect time of year to dive into the history of the Norwegian troll, and what makes them so compelling and beloved. Why do we love trolls?

Two years ago I interviewed Professor Lotta Gavel Adams and artist, architect, and professor Steve Badanes to ask them this question.

The following is a re-post of an article featured in the Norwegian American Newspaper. You can read the original, as well as countless other fascinating articles here on their site.

Trolls have offered a landscape of fascination in Nordic cultures for centuries. Stories of trolls were passed down before folklore was even physically recorded on paper. From parents to children, farmers to townsfolk, troll tales hold a place in history, in Scandinavian history.

What does this long-lasting interest in trolls say about us? How does understanding the concept of what a troll represents help us understand ourselves better? These questions are at the top of mind when we talk about trolls. Professor Lotta Gavel Adams, professor emerita at the University of Washington and Barbro Osher Endowed Chair of Swedish Studies, has garnered a reputation for her knowledge of trolls, specifically through the study of literature.

Gavel Adams has been teaching for over 30 years. When approached to be a part of a lecture series at the National Nordic Museum in Seattle, Gavel Adams suggested a lecture on trolls might be of interest and titled the talk, “Trolls in the Nordic Imagination: Scary, Clumsy, and Lovable.” More than 300 people attended the lecture, and now Gavel Adams and trolls are as synonymous as she is with her main area of research, Swedish playwright, August Strindberg. Even in 2018, the lasting popularity of trolls was evident.

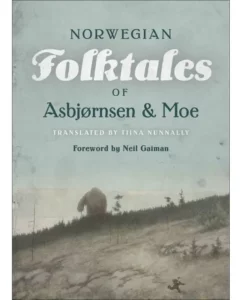

It is impossible to pinpoint the origin of trolls in Nordic folklore. They are physically and historically part of the Nordic countries. Troll stories were an oral tradition, for entertainment and education, especially in rural areas. It wasn’t until the 19th century that two Norwegians, Peter Christen Asbjørnsen, a scholar, and Jørgen Moe, a bishop, sought to collect these stories from Norway and publish them for the world.

Gavel Adams explained that after these tales were collected there was one problem left to solve, “What do trolls look like?” A text was published in 1841, Norske folkeeventyr (Norwegian Folktales) and after reaching international audiences and printing updated editions, the two recruited Norwegian artists to help them depict the mysterious creatures.

Gavel Adams explained that after these tales were collected there was one problem left to solve, “What do trolls look like?” A text was published in 1841, Norske folkeeventyr (Norwegian Folktales) and after reaching international audiences and printing updated editions, the two recruited Norwegian artists to help them depict the mysterious creatures.

How does one draw an imaginary creature that has never been recorded before? Gavel Adams explained that then and now, discrepancies exist in what a troll actually is. Norske folkeeventyr was a collection primarily for adults, but stories about trolls quickly became the subject for children’s books.

“Writers started using trolls as a teaching tool,” Gavel Adams said. And although trolls as children’s content have lasted through the 21st century, with Frozen, Trolls by Dreamworks, Harry Potter, and Moomin, there has also been a return to trolls in adult literature and media.

If you think about depictions of trolls in popular culture, they are all over the map. Are trolls big or are they small? Trolls can be tiny tricksters who live in caves or forest hovels, like many of us grew up with in the works of children’s book author, Jan Brett (Trouble with Trolls, Christmas Trolls). The concept of small trolls is also enforced by the types of souvenirs one might find in a Norwegian gift shop, miniature figures with large noses, wild hair, and big teeth. But animations like 2010’s Norwegian film Trollhunter show trolls more reminiscent of their original stories: large, natural, and ominous.

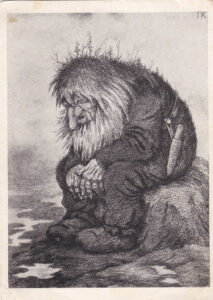

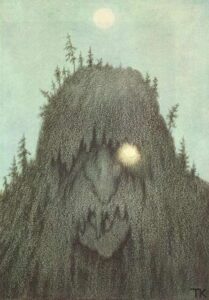

Asbjørnsen and Moe’s later editions of Norske folkeeventyr featured illustrations primarily by the artist, Theodor Kittelsen, who was unknown at the time and brought into the project by his connection to Erik Werenskiold. Kittelsen’s trolls have become one of the most famous depictions in Norway and the world. Closer to the legends of giants, like those from Jotunheimen (the home of the giants), Kittelsen’s trolls could be mistaken for mountains or trees, save for one or two glimmering eyes. The trolls come out of the earth and if you find yourself in the forest or a rocky fjord, you yourself might be able to spot one. “They merge out of nature,” Gavel Adams said. This is the magical feeling Kittelsen’s trolls evoke.

Another lasting legend surrounding trolls comes from the Christianization of the Nordic countries. Trolls became associated with the devil, Gavel Adams explained, “If you hold up a cross, they will turn to stone or disappear.” Several natural sites are named after trolls in Norway. Trolltunga (the troll’s tongue) is a hiking destination outside of Odda, which looks like a large stone tongue. Landmarks like these feed the myth that some large trolls were turned into rocks and any boulder or hill could have previously been a troll.

In the United States, there’s one famous stone troll, and that is the Fremont Troll in Seattle’s Fremont neighborhood. This public sculpture has become a cultural icon.

The larger-than-life troll was born out of a need to eliminate crime under the Aurora Bridge. In 1989, The Fremont Arts Council held a competition, after receiving a grant from the Department of Neighborhoods for a piece of public art to occupy the space. Architect Steve Badanes was invited to enter a project with three collaborators: his partner, Donna Walter, and two students at the University of Washington, Will Martin and Ross Whitehead.

After visiting the space, Badanes said, “I went over to the site and I looked at it and after about 15 seconds you look under a bridge and you go, a troll. That old story of the troll under the bridge is just lodged in your brain. But I had no idea what they would look like.”

After doing some research, the team made a model of the troll and with a sweeping six-to-one vote, won the public vote for the installation. Built with a tight budget, urbanite donated by the City of Seattle, and volunteer labor, the Fremont Troll was finished in a couple of months. “The Three Billy Goats Gruff” is a Norwegian folktale, and although it was part of the inspiration for this piece, Badanes insists that no goats or other “cornball stuff” will be added to the park. “The cruddiness of it … is part of the ambience,” Badanes said.

The half-submerged sculpture is reminiscent of a Kittelsen troll, visually coming out of the ground. The only details are the hair, fingers, and nose (modeled after Badanes). It’s simple and made to last. According to Badanes, the Fremont Troll is annoyed, which is why he’s clutching a Volkswagen Bug he may have snatched from the bridge above. “The trolls’ worst enemies are development and pollution, and they’re very peaceful, unless they’re aroused.”

Trolls represent the anti-hero. This troll might have driven out crime and pollution under the bridge, but the sculpture was made by artists during a time when many were being driven out of gentrifying neighborhoods. Badanes said, “The troll was kind of a protest against that. That was the idea. Against development. A lot of people don’t always get that statement, but that is what was intended. As long as people enjoy it, everything is fine.”

The Fremont Troll continues to be a hugely popular tourist attraction, bringing visitors to the area daily. Halloween, or “Trolloween,” is the official birthday of the Fremont Troll, and it turned 30 in 2020.

In Norway today, you will still find signs indicating a troll crossing, and “where can I see trolls in Norway?” is a top Google search. Copenhagen artist Thomas Dambo has become famous for his recycled wood troll sculptures, installed in natural environments around the world.

Humans seek out trolls to understand them. While they provide lessons, comedy, and hope, we never fully will. The trolls will always be one step ahead, looking back from behind a tree.

Loved reading this. I collect gnomes as there aren’t many trolls in US .