Where did designer Mary Jane Mucklestone find the 150 Scandinavian Motifs in her latest book?

“When I go to yard sales, I always get old knitting patterns,” she says. “And growing up in Seattle, I saw everything on my schoolmates’ backs,” a parade of reindeer, eight-petaled roses, and “lice.”

She saw those design elements again in embroideries at home from her Norwegian great-grandmother. And again on trips to Scandinavia. And eventually in favorite books by Annemor Sundbø and Vibekke Lind.

What clearer sign could there be of Scandinavia’s influence on Mucklestone than her very first knitting project at age 5? A blanket for her troll doll.

What clearer sign could there be of Scandinavia’s influence on Mucklestone than her very first knitting project at age 5? A blanket for her troll doll.

Today when she visits Seattle from her home in Maine, as she did for a research trip to the Nordic Heritage Museum, she hunts for vintage Nordic knits on thift shop racks. “My daughter is also a collector of them and she scored big time last time she went to Seattle.”

Scandinavian motifs “just float around” in some cities, Mucklestone says. They’re like an echo of the immigrants who settled there. But her goal with the book wasn’t to create a record of the past.

“All these kinds of traditions, all handwork, I think, is evolving,” she says. “It never stays the same, because people change and the materials that are available change.” By collecting motifs, she wanted to open a window into Scandinavian design as a “living tradition.”

“All these kinds of traditions, all handwork, I think, is evolving,” she says. “It never stays the same, because people change and the materials that are available change.” By collecting motifs, she wanted to open a window into Scandinavian design as a “living tradition.”

An encouraging teacher, Mucklestone is enthusiastic when she looks at photos of what I knit from her book using motifs 25 and 26 and Falk yarn from Dale of Norway: “I love your pillow. Exactly how I envisioned my book being used.”

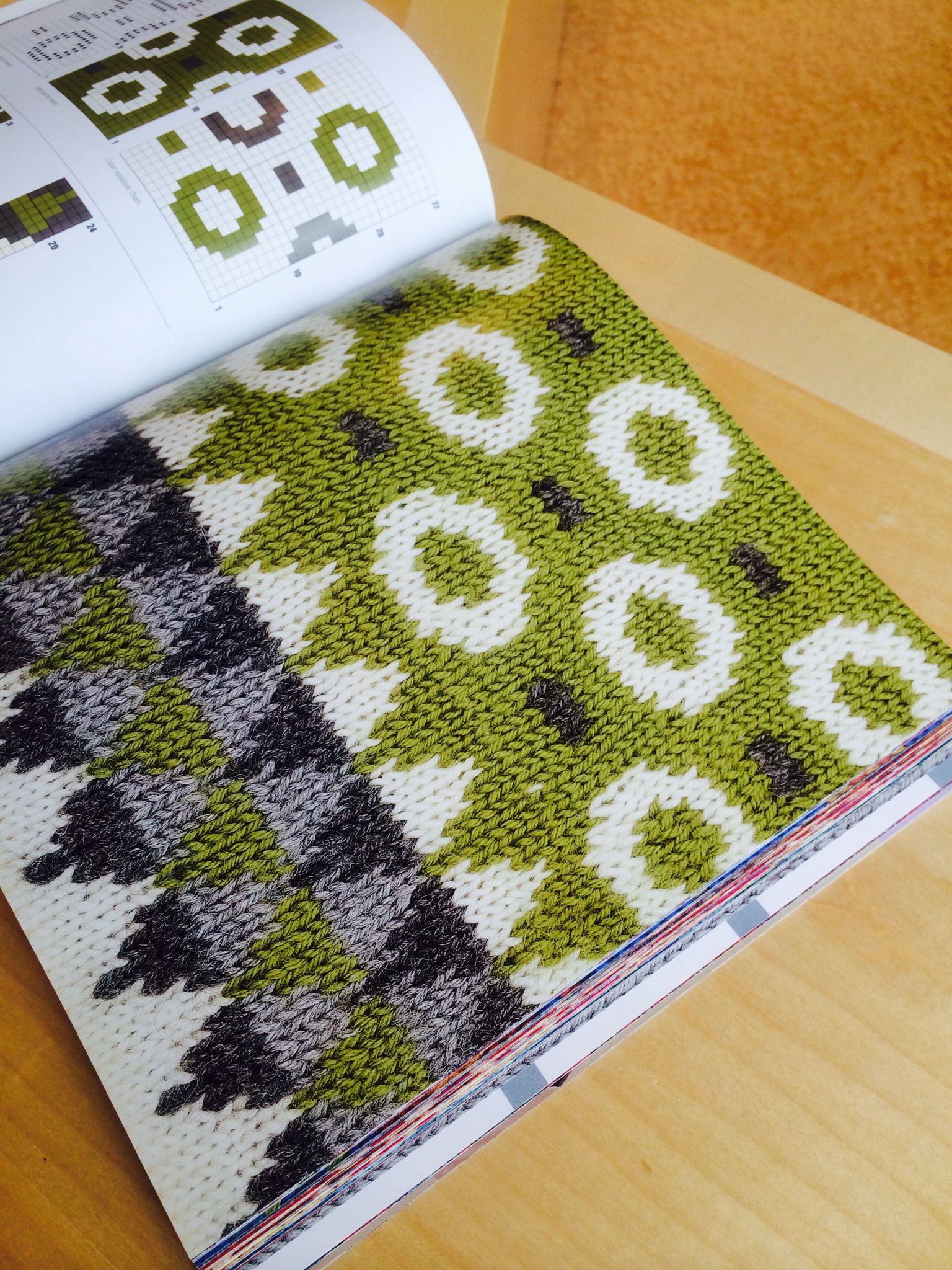

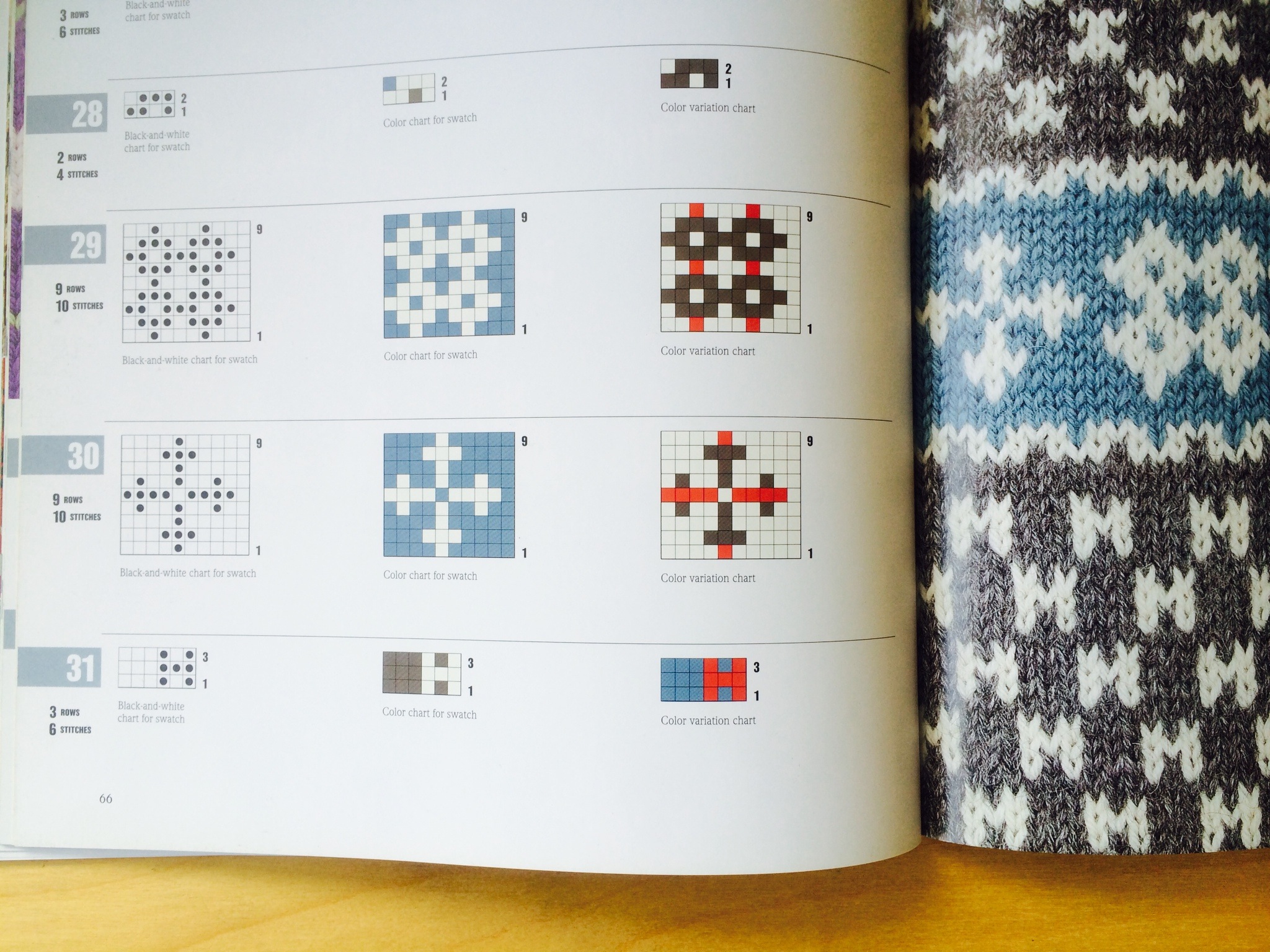

There is no pillow pattern per se in the book, but it’s easy to pick motifs that you like and put them to use, especially in a simple shape like a pillow. Each motif is well charted—in black and white, in color, and in variations to encourage you to experiment—and each one is labeled with the number of stitches and rows it contains. Mucklestone has excellent notes at the front of the book on how to adapt motifs to anything you want to knit, from doing the math to placing the shapes in a balanced way on a garment.

There is no pillow pattern per se in the book, but it’s easy to pick motifs that you like and put them to use, especially in a simple shape like a pillow. Each motif is well charted—in black and white, in color, and in variations to encourage you to experiment—and each one is labeled with the number of stitches and rows it contains. Mucklestone has excellent notes at the front of the book on how to adapt motifs to anything you want to knit, from doing the math to placing the shapes in a balanced way on a garment.

Her own preference is not for “the really old patterns, but more the 1960s designers,” and that’s how the circle motif in my pillow came about, she says. She created it herself in the spirit of an evolving tradition.

“It said ‘modern Scandinavia’ to me in that it was really graphic,” she says. “I had done those flowers that seem really, really modern, but aren’t, on page 136 . . . . The one down in the righthand corner? I riffed on that circle in the center of the flower” to make the circles in motif 25.

An artist by training, Mucklestone studied printmaking at New York’s Pratt Institute, and elsewhere studied textile design and historic costumes. Knitting didn’t really take hold in her life until she moved to Maine to start her family and decided yarn was environmentally friendlier than the inks and dyes she’d been working with.

“All that stuff is pretty toxic, and we had our own well, so I didn’t feel comfortable dumping anything down the drain,” Mucklestone says. “Knitting was pretty green, comparatively.”

Now she’s known for vibrant knitwear designs that have appeared in Interweave Knits and other magazines and books. She’s known as an inspiring teacher, too. Technique-wise, she says four things really matter when working with Scandinavian motifs.

First, “it’s essential to swatch,” because each motif will have a different affect on your gauge.

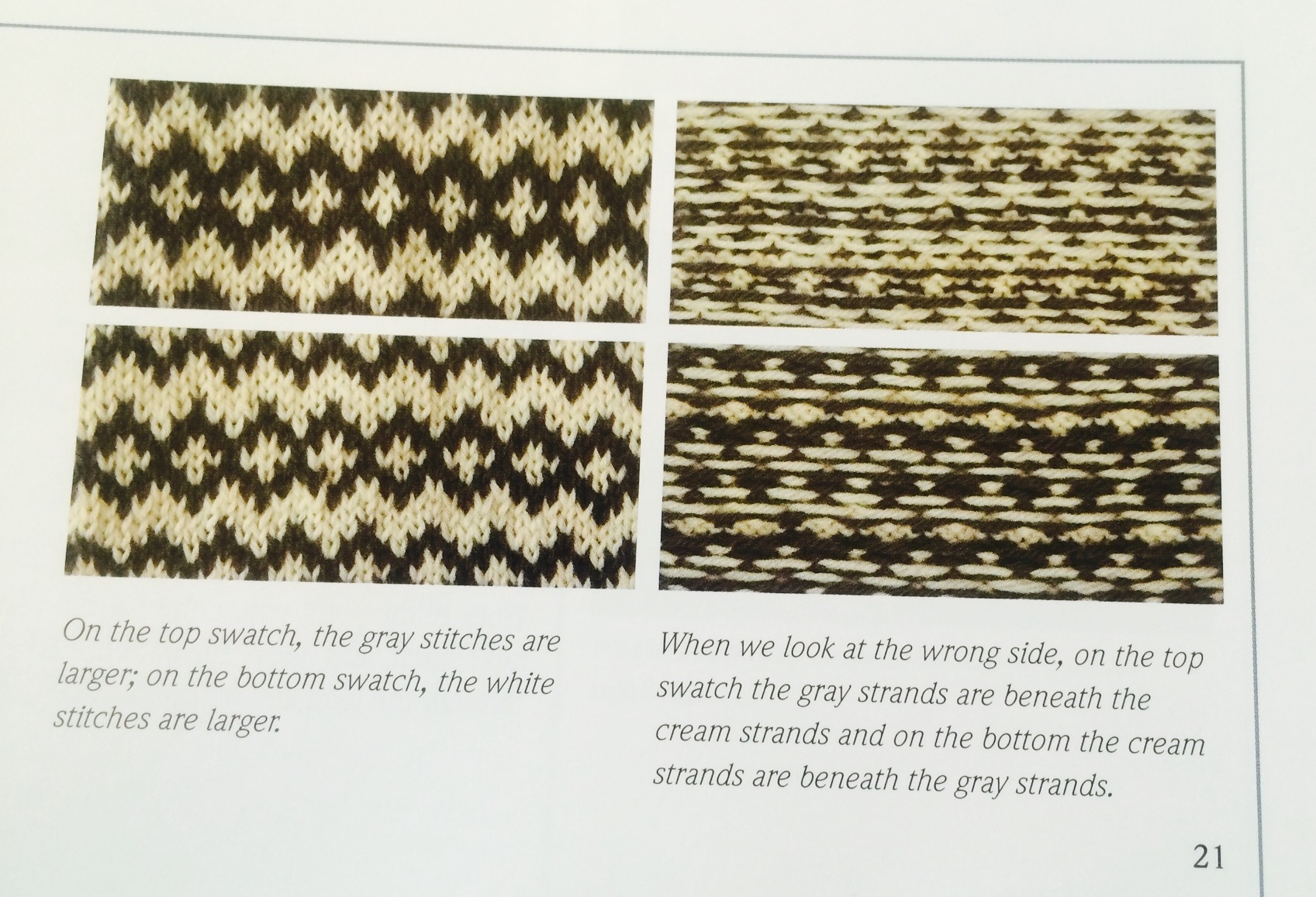

Swatching will help you with another variable, “yarn dominance,” Mucklestone explains, and a set of photos in her book makes this clear. A color that’s carried for long stretches along the back of the work, or carried in one hand versus the other, can tend to make slightly tighter, smaller stitches that recede on the front of the work. Meanwhile, a color carried in the opposite hand, or simply used more frequently and carried for shorter distances, might make looser, fuller stitches that appear dominant on the front of the work.

“But it will be different for everybody, so the most important thing is just to be consistent,” Mucklestone says. “If you assign a color to one hand, keep it there throughout the garment.” Swatching will show you “which position of holding the yarn is most dominant for you.”

A third tip: You can avoid tight “floats” of yarn on the back of your work if you “spread the just-knit stitches out along your righthand needle,” as they would be in the finished item. “People tend to bunch them up there . . . and that will make the float too small.”

A third tip: You can avoid tight “floats” of yarn on the back of your work if you “spread the just-knit stitches out along your righthand needle,” as they would be in the finished item. “People tend to bunch them up there . . . and that will make the float too small.”

Finally, she says, try not to get too caught up in your charts, or it’s easy to lose track of how your new stitches are fitting in with what you’ve already knit.

“I always cover the chart [that I’ve knit so far] with a really cheap Post-it note that you can see through, so I can see where I’ve been. But most importantly, I’m looking at my own work so I know what’s in my hands.”

– Denise Logeland

– Denise Logeland