The meeting of Celtic and Finnic culture on the Iron Range gave the world more than the redoubtable St. Urho. It was also the catalyst for the creation of the U.P. pasty – a semicircular pastry crust that holds a filling of meat, potatoes, rutabagas, and carrots. “The Cornish may have developed the pasty, but the Finns of the Iron Range made it their own,” says Yvonne Lockwood, Finnish-American folklorist and curator emerita of Folklife at the Michigan State University Museum. Jonathan Rundman also Finnish-American and a scholar of Finnish Lutheran culture, agrees. “Pasties are part of the social fabric. Finnish churches gather for a weekend to make and sell pasties. High school sports teams make and sell them. They’re labor intensive, so it’s never wise to make pasties alone. People find reasons to get together to have a pasty party.”

The meeting of Celtic and Finnic culture on the Iron Range gave the world more than the redoubtable St. Urho. It was also the catalyst for the creation of the U.P. pasty – a semicircular pastry crust that holds a filling of meat, potatoes, rutabagas, and carrots. “The Cornish may have developed the pasty, but the Finns of the Iron Range made it their own,” says Yvonne Lockwood, Finnish-American folklorist and curator emerita of Folklife at the Michigan State University Museum. Jonathan Rundman also Finnish-American and a scholar of Finnish Lutheran culture, agrees. “Pasties are part of the social fabric. Finnish churches gather for a weekend to make and sell pasties. High school sports teams make and sell them. They’re labor intensive, so it’s never wise to make pasties alone. People find reasons to get together to have a pasty party.”

In the beginning…

Pasties originated in Cornwall, England, the southwest peninsula that juts out into the Atlantic. Americans know the region as the setting for the BBC’s Doc Martin and Poldark series. The Cornish are ethnically Celts. They have their own culture and language (which is undergoing a revival), were skilled miners, and knew how to make a sustaining lunch.

Meat pies were made in Britain from at least the 1100s. Often a combination of venison and seasonings in a sturdy crust, the pasty became an entity unto itself in Cornwall. There it became a miner’s lunch: a complete meal in a giant semi-circular pastry, self-contained and easy to eat even in the difficult environment of being underground. Wrapped in warm towels or newspapers and kept in tin lunch buckets, pasties would stay warm for hours. If they did cool off, they could be heated over a miner’s lantern.

The pasty diaspora begins

The demand for miners from the 1830s onwards created opportunities for the Cornish in the United States, Mexico, Australia, and South Africa. They brought their pickaxes and their food ways with them. Cornish pasties are now designated as a protected cultural food by the European Union. The EU specifies exact guidelines for what constitutes a Cornish pasty, detailing ingredients and appearance. Pasties in their new homes abroad, however, vary.

All pasties, wherever they’re made, have a thick, crimped edging that seals the semi-circle of dough. Cornish women had a very specific style of crimping the pasty, while the Finnish women did not. Some food historians believe the thick crimping around the edges served as a handle that allowed the miners to safely eat their lunch. Washing one’s hands was clearly impossible in that setting and a miner would often have dirt containing arsenic and lead on his hands. If he held the thick crimped crust, he could eat the center safely. Other historians think that the crimping was simply to seal the pasty. The miners could have wrapped a corner of the pasty in the newspaper or towel they used to keep it warm. They could then eat the pasty from end to end.

Well, it sounded like a good story

I like the thick-crust-for-safety story, so I am going to perpetuate that version. I am also going to repeat the story that the miners would leave the crusts in the mine to placate the trolls and mine ghosts that lurked underground. Yvonne Lockwood pointed out that it would be simply sensible to leave a lead-tainted bit of lunch behind, trolls or no trolls. She also said that the stories of Finnish women going to the mines at lunch time to throw pasties down to their husbands were fictitious. She says, “There is no pastry strong enough to withstand being tossed to the bottom of a mine. And if there was, who would want to eat it?” Fair point.

Fuel food

Pasties became popular as miners’ fare not only because they were easy to eat, but also because they were highly caloric. Though that’s not a selling point in this era, the men needed the energy. When trying to determine how many calories a miner would burn in a day, the closest equivalent I could find was calories burned while chopping wood – a 140-pound person chopping wood vigorously would burn 535 calories an hour. Calculate that for the usual 10-hour shift miners worked, that’s 5,350 calories. Research leads to entertaining rabbit holes, so I am happy to share a useful guide I found on how to chop one’s way to better core muscle strength and weight loss. It may be useful information after a pasty binge.

The contact point

The point of pasty cultural exchange happened when experienced Cornish miners and engineers came to the northern Midwest’s Iron Range to develop the vast copper and iron deposits there. Finnish and Italian immigrants soon followed. One theory is that the newer immigrants wanted to imitate their more assimilated supervisors and foreman and have food just like them.

More likely, a Finnish miner came home and said to his wife that he saw a Cornish co-worker with a lunch that looked really good. “If that woman were me, I’d go over to a Cornish woman’s house and ask for the recipe,” laughed Yvonne Lockwood in a telephone interview. “The Finnish and Cornish women probably didn’t interact very much, but sharing recipes and food ideas crosses cultures and social status.” Jonathan Rundman believes it was simple practicality that caused it to be adopted by the Finns and Italians. “The pasty is easy to eat and is a triumph of form and function,” he says.

The U.P. pasty begins to evolve

Once the Finns got hold of the idea, subtle but important changes were made. In Cornish pasties, the vegetables were sliced, or “chipped.” Finns diced theirs and they added carrots, while Cornish pasties were strictly potato and rutabaga. Cornish women put a pat of lard on the filling before closing the pasty, while Finnish cooks used butter.

The meat varied with what was available. Game was, and still is, an important source of protein. “People in northern Michigan have a chest freezer, then a separate industrial freezer for hunting camp and pasties,” says Jonathan. Venison is a popular choice of meat, just as it was in medieval England. Yoopers have been playing fast and loose for decades with other ingredients and have many tasty variations, though Jonathan declares pizza pasties “completely blasphemous.”

Pasty making is truly best as a party

Jonathan’s mother, Mary, kindly shared her recipe for pasties with me. I didn’t take Jonathan’s advice to gather friends and have a party. I tried making them all on my own. The process and product were OK, but not anything that did justice to Mary’s recipe. It was time for a tutorial.

I asked Cynthia Lillquist of Epworth United Methodist Church in south Minneapolis if I could join the kitchen crew of experienced volunteers as they made close to 400 pasties as part of their twice-yearly fundraiser.

Cynthia, who leads the project, welcomed me and told me the tradition started 40 years ago when a member of the congregation, Verna, a transplant from the Iron Range, had suggested pasties as a fundraiser. The church uses Verna’s original recipe, plus a vegetarian recipe they developed. The process, honed through the decades, was impressively smooth. The kitchen crew ranged in age from 10 to over 70, all patient teachers (with special thanks to Judy) and all had valuable tips to share.

Here are the key takeaways:

- You can dice the rutabagas and carrots and store them in the refrigerator up to 4 days before assembling the final product. (A day ahead is preferable, but scheduling a pasty party can be difficult.)

- Use Crisco in the pastry. Mary Rundman was also specific on this point. Other shortening brands just do not give the same result.

- You can mix the Crisco and flour a day ahead of assembly. Add the water and make the pastry when you are ready to roll and shape the dough.

- After adding the water to the flour, work the dough only enough so the all the flour is incorporated. Then leave it alone. (Overworked dough gets tough, making rolling and filling a challenge.)

- Make the pasty dough 6 to 8 inches in circumference. Larger than that, the pasty falls apart under the weight of the filling. The Epsworth UMC crew used 8” plates as a handy guide for rolling and cutting. No special equipment needed.

- Make sure the pasty is sealed, especially the corners. The folds don’t have to be Great-British-Bakeoff-perfect but they do need to keep the juices inside. Double-check corners before putting the pasties in the oven.

- When you take a tray of pasties out of the oven, hold it a few inches over the counter, then drop it. This shakes the pasties loose and you don’t have to worry about cutting into one with a spatula when lifting it off the tray.

- Pasties freeze well. While miner’s wives may have made pasties fresh every day, you can make a large batch, freeze some, and portion them out for months afterwards. Thaw before reheating in the oven.

How do you top a pasty?

When eating a pasty at home and not underground in a mine, you have several options for topping it. The recommendations from the Epworth experts are as follows:

- Catsup (Quite traditional)

- Brown gravy. Homemade is best, but if you’re hungry and desperate, gravy from a jar will do.

- Cream of mushroom or cream of celery soup that has been thinned with milk to a gravy-like consistency. Recommended proportions are one can soup thinned with ½ can milk for 2 pasties.

Other ideas and polite opinions on toppings are welcomed in the comment section.

If you want to be a pasty apprentice or to just buy them:

The Epworth United Methodist Church sells pasties twice a year. If you would like to volunteer or order pasties from their upcoming fall sale in November, click here to go to the website and their contact information.

Vær så god!

Hyvää ruokahalua!

U.P. Pasty for Ingebretsen's Food Blog

Ingredients

Filling

- 12 small potatoes cubed

- ½ large onion cubed

- ¾ rutabaga cubed

- 2 carrots cubed (optional)

- 1½ lbs. fatty ground beef

- ¾ lb. ground pork

- salt and pepper to taste

Pastry

- Make the dough in thirds so it is easier to handle.

- 9 cups all-purpose flour

- 3 teaspoons salt

- 2 cups Crisco

- 15 tbsp warm water

Instructions

Filling

- Dice the vegetables into ⅛ to ¼ inch cubes. Place in a large bowl.

- Add in the ground beef, ground pork, and seasonings. Set bowl aside.

Pastry

- Mix the salt into the flour.

- Cut the Crisco into the flour and salt mixture. You can use a pastry blender or two table knives to do this.

- Slowly add the water. Mix lightly with your hands or a fork. Stop adding water once the dough forms a ball.

- Roll out each fourth on a lightly floured surface until it is roughly 8" in circumference. Use an 8" plate as your guide for cutting and trimming the dough.

Assembling

- Set out the twelve dough circles. Divide the filling between the dough circles. Place the filling on one half of the circle.

- Put a pat of butter on top of the filling on each pasty.

- Pull the dough from one side, up and over the filling, and press the edges together.

- And now, the crimp! Fold and pinch along the edges of the semi-circle, with special attention to the corners.

- Cut two small vent holes in the sealed pasty.

Baking

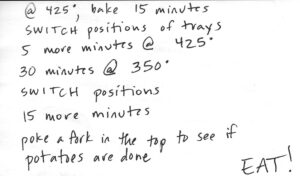

- Pre-heat oven to 425℉

- Divide pasties onto two trays.

- Bake for 15 minutes.

- Switch the position of the trays. Bake for 5 more minutes.

- Turn oven down to 350℉

- Bake for 30 minutes. Switch tray position.

- Bake for 15 minutes. Test with a sharp knife to see if the vegetables are tender.

- Cool for ten minutes on the tray. To remove the pasties, hold the tray several inches above a counter, then drop them. This will loosen them from the tray. The pasties can be eaten hot, cold, or frozen for later use.

Thank you for posting this recipe. I have long been curious our these and look forward to trying it. They kind of remind me of the calzone our pizzeria makes but with different ingredients.

Yes, pasties and calzone are both filling and comforting. Please let us know how the pasties turn out when you try the recipe.